Insights

Insights

What is Success?

The central challenge of this question lies in the agency theory. The agency dilemma arises when the capital provider (principal) is separated from the management (agent). This leads to an unequal distribution of information, as the capital provider often has only incomplete information about the company’s performance. Such situations occur, for example, when the founder of a family business steps back to the Board of Directors («Board») and hands over the management to an external, non-family manager. This creates information asymmetries between the owner and the new manager. There are various ways of reducing these asymmetries, such as control, monitoring and financial incentive systems.

The company performance is of central importance in incentive systems. This raises the question of how the owner or the Board can conduct a comprehensive and systematic assessment of the company’s performance. Is the observed performance good or bad? How should non-financial factors be included in the performance assessment?

The starting point to determine «What is success?» is the purpose of the business. If executive team members are asked individually, the chances of getting a range of very different answers are high: Ensuring customer satisfaction, providing secure jobs, creating added value for shareholders and customers, making a positive contribution to society etc. All these factors are relevant, but with so many financial and non-financial interests, goals and intentions, the question arises: What priorities should be set?

In the last decades, prioritisation was set according to the shareholder value maximisation approach. Put simply: «If the shareholder is doing well, everyone benefits». However, the implementation of this construct often resulted in losing the focus on important long-term aspects of the company’s development. Since the financial crisis of 2008, it has become clear that a one-sided focus on the share price and key financial figures is not sufficient to reflect sustainable corporate development.

There is a growing realisation that, besides the financial indicators, other aspects such as quality, long-term supplier relationships, employee and customer satisfaction, etc. are important for the top-level steering of the company. However, these aspects are often neither sufficiently nor systematically included in the performance assessment.

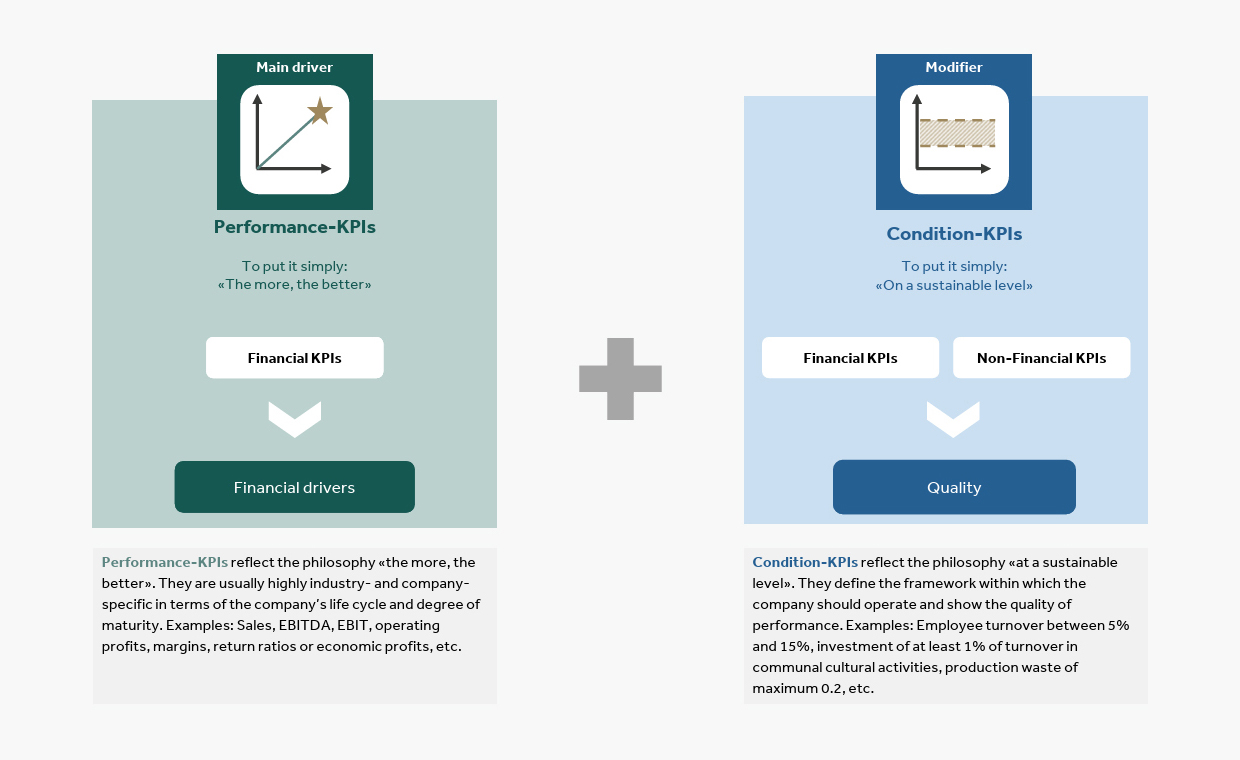

Another challenge is the conflicting objectives between the KPIs: Should prices be reduced in order to increase customer satisfaction? Should employee satisfaction be improved, or should costs be reduced? Such trade-offs are common in everyday business life. But how can one KPI be weighed against another? Often, numeric weightings are introduced to address this issue. However, this does not solve the dilemma, as many KPIs are not truly performance drivers per se, but rather represent conditions and prerequisites for sustainable performance. Therefore, we differentiate between Performance-KPIs and Condition-KPIs; for example, in profit-sharing schemes.

Performance-KPIs vs. Condition-KPIs

The Condition-KPIs act as a «modifier» to the overall performance assessment derived from the Performance-KPIs. In other words, the underlying firm performance is assessed based on Performance-KPIs, while the financial and non-financial Condition-KPIs serve as a modifier. Typically, the modifier can lead to an adjustment of the Performance-KPIs by around plus/minus 20% to 30%.

Condition-KPIs are often mistakenly treated like Performance-KPIs, meaning that targets are set, and deviations are measured. However, this is an inappropriate approach for Condition-KPIs. This is because they represent framework conditions and, therefore, need to be treated differently.

Measuring deviations is not suitable for Condition-KPIs, as deviations suggest that more or less is automatically better or worse, which is not necessarily the case. For Condition-KPIs, it is much more important to be for example within a range. This range helps to ensure that small changes do not have immediate consequences. The principle is as follows: As long as the Condition-KPI is within the range, it is good enough. Thinking about quality in terms of ranges, minimum and maximum requirements enables entrepreneurial performance discussions without conflicting objectives.

«Quality Scorecard»

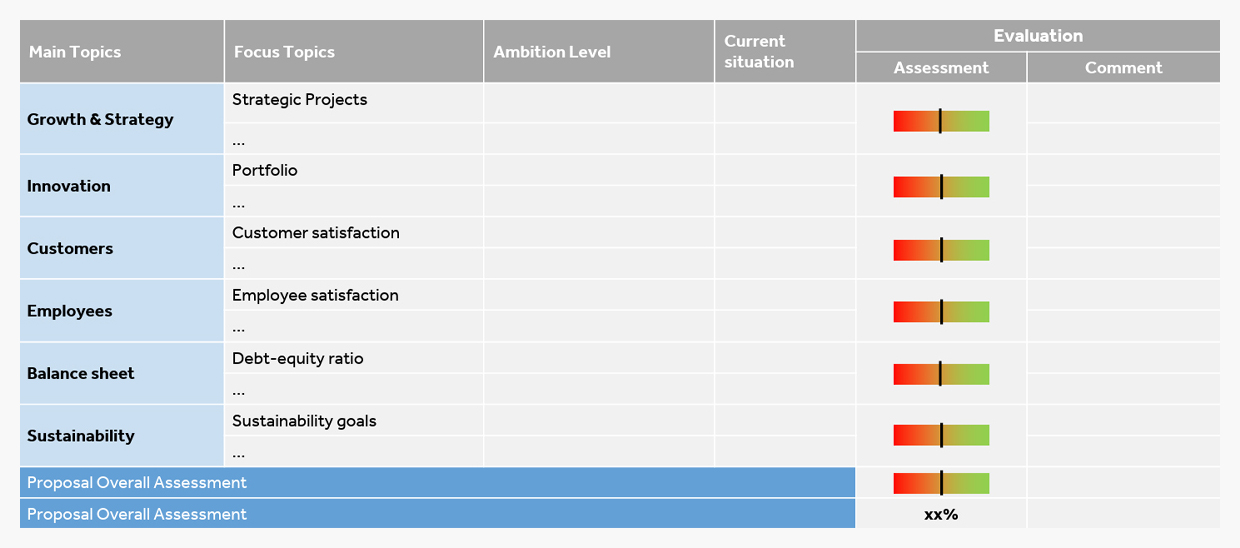

How do owners, Boards and management determine the «conditions» for long-term profit? It is often mistakenly assumed that a large and almost unmanageable number of topics and factors are relevant. In practice, however, the Condition-KPIs can be summarised in five to six main topics, such as growth and strategy, innovation, customers, balance sheet and sustainability.

These main topics differ only slightly between small and large companies. Owners who are actively involved in the company’s operations have a good grasp of the relevant information and can quickly assess whether the financial performance is robust and sustainable. But how can Condition-KPIs be made more understandable and tangible for the Board members who are less involved in the company and not operationally active?

Summarizing Condition-KPIs in a «Quality Scorecard» is one way of addressing quality factors systematically and effectively. It also makes Condition-KPIs easier to understand for the Board and the management. Additionally, it establishes a common language between operational management and the Board about what constitutes «success» in the organisation.

The «Quality Scorecard» is designed as follows: Firstly, the focus topics are collected and consolidated. The focus topics are then assigned to the main topics and supplemented with corresponding ambitions. It should be noted that the strategic relevance of the focus topics and their ambitions should be reviewed periodically, while the main topics remain rather constant.

This is followed by a compilation of certain information on the current status, and lastly, the company’s performance is commented and assessed by using a slider on a colour-coded bar. Focus topics that cannot be measured quantitatively should also be included in the «Quality Scorecard», as they are often not «measurable» but can be «assessed». This creates the necessary scope for owners and the Board to systematically address such topics.

The «Quality Scorecard» should be summarised so that it fits within a single page. It also makes sense to take up the topics, for example, at quarterly Board meetings and provide a brief update. This will prevent the Board from an information overflow during the annual performance review at the end of the year.

Conclusion

Equal pay has become a largely discussed topic in the regulatory environment of many countries. At the same time, an increasing number of companies have acknowledged the importance of equal pay and diversity as an integral part of their culture. However, most countries still show a relatively high gender pay gap with a substantial unexplained part. As Swiss companies with more than 100 employees are required to conduct an equal pay analysis starting this year, they are well advised to leverage equal pay and related initiatives as an opportunity for change to execute their talent strategy and to eventually gain from the positive effects of diversity on performance.

Next to transparency and pro-active communications regarding pay practices, all companies can benefit from the introduction of initiatives to hire, retain, and actively develop more women on all organizational levels. Going a step further, gender representation and pay gap outcomes can be considered in performance management processes. Such initiatives facilitate a culture of diversity and inclusion and are not only expected to have a positive impact on the employer’s attractiveness for talent in the future but also contribute to its positioning towards investors and will increase the company’s value in the long run.